4/11 2015, Den otevřených dvěří Ateliéru intermédií FaVU VUT Brno, 13:00–19:00, Údolní 19.

První ateliérová schůzka je ve středu 23/9 13:00, místnost 316 (Údolní). Prosíme o dochvilnost!

Novým vedoucím ateliéru bude od 1. září 2015 umělec Pavel Sterec.

Karel Císař: Umění ztrácet | The art of losing

Umění ztrácet

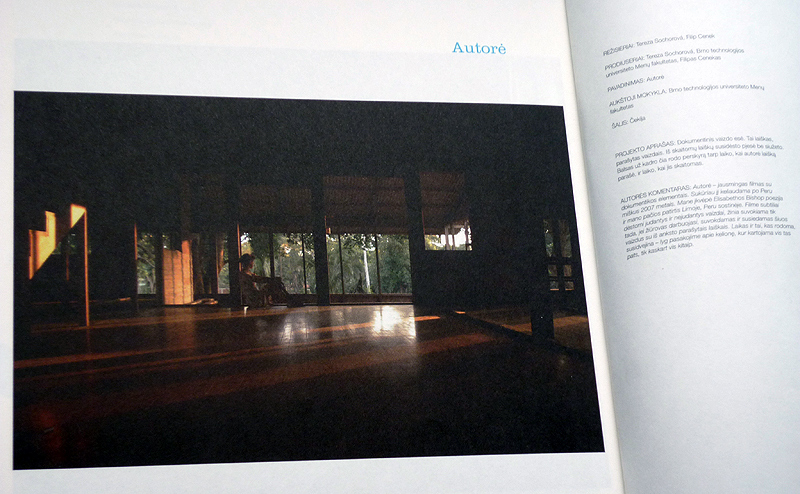

Šedesáti sekundová sekvence mezi 2’10 a 3’10 minutou videa Spisovatelka Terezy Sochorové a Filipa Cenka zachycuje pohled do dvorany hotelu Sheraton v peruánské Limě. Ve statickém záběru se před námi postupně rozsvěcuje rýhování ochozů jednotlivých pater, a teprve pak se kamera pomalu vydává směrem vzhůru. Letmo se zastaví ve chvíli, kdy se do středu obrazu přesunou zářící body stropního osvětlení, jakoby kamera dosáhla vrcholu výškové budovy, k němuž jí však ještě několik pater zbývá. Byl-li pohyb vzhůru snímán ve velkém celku, pohyb směrem dolů je zachycen ve velkém detailu tak, že se v rychlém sledu míhají hotelové zářivky. I v tomto případě se pohyb zastavuje těsně před tím, než se světla ztrácejí z dohledu. Osové dělení a zmnožování je vepsáno i do bezprostředně předchozích a následných záběrů videa. Nejprve podle logiky vertikální osy vstupuje do záběru procházející muž a v odlesku skleněných dveří se do něj obratem z druhé strany vrací. Horizontální osa odděluje jiného procházejícího muže od jeho odlesku na mramorové podlaze. A konečně lesk mosazného kování zdvojuje ruku, která tlačítkem přivolává výtah. Princip zdvojení neovládá pouze prostorovou, ale i časovou osnovu videa. Zvonek ohlašující příjezd výtahu zaznívá znovu a opakovaně zabliká i rozbitá zářivka na chodbě hotelu.

O tom, že tento princip není zvolen nijak náhodně, nejlépe svědčí významové těžiště práce, které je třeba hledat v detailním záběru na báseň v knize, položené na stolku v hotelovém pokoji. Jedná se o báseň Jedno umění od americké modernistické spisovatelky Elizabeth Bishopové. Zvlášť důležitá je z tohoto hlediska forma – je jí villanella, náročný básnický tvar, složený z šesti trojverší a jednoho závěrečného verše. A podobně jako se v básni Jedno umění opakují rýmovaná slova, opakují se ve videu Spisovatelka záběry se zdvojenými obrazy. Rytmickému pohybu pater ze sekvence z hotelové haly odpovídá i rytmus, jímž je video členěno do několika oddělených částí. Souvislost Spisovatelky s Jedním uměním ovšem není pouze formální. Bishopová píše o „umění ztrácet“ a od běžné ztráty věcí či směru se dostává k ztrátě blízkého člověka: „The art of losing isn‘t hard to master; / so many things seem filled with the intent / to be lost that their loss is no disaster. //...// – Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture / I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident / the art of losing‘s not too hard to master / though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster. „Umění ztrácet, zvládneš bez bolesti; / věci jako by chtěly ze všech sil / se ztratit, takže není to neštěstí. //...// – I ztratit tebe (s veselým hlasem, s gesty, / co mám tak ráda); kdo by nevěřil, / že v umění ztrácet není moc bolesti, / i když vypadá to (Piš si!) jako neštěstí.“ (přel. M. Housková)

Význam básně je skryt ve vnitřní semknutosti umění a ztráty, plnosti a prázdnoty. Bolest nad ztrátou blízkého se Bishopová pokouší vyvažovat zvládnutím básnické formy, která se však v závěru zcela hroutí. Stejně tak ovšem platí, že každé psaní představuje jistou ztrátu, neboť syntax s sebou nese přijetí prázdna jako nikoli vnější, nýbrž vnitřní podmínky každého smyslu. Toto napětí je ještě umocněno volbou dvou hlasů, kterými se na nás spisovatelka obrací: v prvních třech trojverších je to hlas ve druhé osobě singuláru, ve druhých třech trojverších hovoří sama k sobě v první osobě. V posledním, přidaném, verši se ve vložené formulaci v závorce – ještě zdůrazněné užitou kurzivou („Piš si!“) – na okamžik vrací druhá osoba. Ambivalentní sepjetí mezi uměním a ztrátou, mezi spojením a rozdělením, je v posledním verši přítomno v samotném zápisu básně, když Bishopová strofu rozbíjí vloženou závorkou a zdvojeným „like“.

Stejně zdvojený je i hlas videa Spisovatelka. Neutrální statické záběry jsou v první části prokládány těkavými subjektivními pohledy, neboť obrazový deník z cest odpovídá cestovatelsky deskriptivnímu stylu Bishopové ze sbírek Otázky cestování (1965) a Zeměpis III (1976), z níž pochází i Jedno umění. V druhé části videa se subjektivní pohledy z okna hotelu staly podkladem k četbě dopisu z Limy. Právě dopis představuje „umění ztrácet“, neboť při jeho psaní jsme u osoby, která jej později bude číst, a naopak ten, kdo jej potom čte, vzpomíná na toho, kdo jej psal. I proto je hlas dopisu ve videu zdvojen, když jej nejprve čte pisatelka, pak adresát a potom jejich hlasy zazní i v souzvuku. Roli osamělého imperativu „Piš si!“ ze závěru básně v dopise zastupuje závěrečné „Ty víš“. Téma vztahu však nejsilněji vytane v poslední části videa, složené ze statických snímků čekajícího muže a ženy. Jako se dopis obracel k předchozí části, když popisoval příjezd do hotelu, předjímal totiž zároveň i část závěrečnou. Zatímco vyčkávající muž před domem hledí směrem do kamery, žena je v dialektickém prostřihu snímána uvnitř domu zezadu, jako by se obracela k němu. V prvním snímku se žena pravou rukou zlehka opírá o rám dveří a pravou nohu má pokrčenou, jak tomu bývá při dlouhém čekání. V závěrečném záběru ji již vidíme opřenou o stěnu, její pohled je však stále upnut směrem ven, jak je patrné z napjaté šíje: „Osamělá spisovatelka“.

— Karel Císař [in: Labyrint revue č. 31–32 (2012), Labyrint – Via Vestra, Praha, 2013, str. 88. ISSN 1210-6887]

Tereza Sochorová & Filip Cenek: Spisovatelka (2008, video, 9:15 min.)

Video (on-line): http://intermedia.ffa.vutbr.cz/spisovatelka-authoress

The art of losing

A sixty-second sequence, the 2’10 and 3’10 minute of the Authoress video by Tereza Sochorova & Filip Cenek, shows a view of the Sheraton Hotel lobby in Lima, Peru. In a static shot the floor landings light up one after another in front of our eyes before the camera slowly starts to pan upwards. It briefly stops at a moment when the shining spots of the ceiling lighting shift to the centre of the view, as if the camera has reached the top of the high rise although in reality it still has to negotiate a few floors to get there. While the upward movement was filmed as a distant shot, the downward motion is captured in great detail so that the fluorescent lamps in the hotel flicker in a fast sequence. Again, the movement stops shortly before the lights are lost from view. The axial division and multiplication is also inscribed into the immediately preceding and following video shots. At first, by the logic of the vertical axis a walking man enters the shot, returning to it from the other side in a reflection of the glass door. The horizontal axis separates another man walking by from his reflection on the marble floor. And finally, the sheen of the brass metalwork doubles a hand which calls a lift by pressing a button. The duplication principle does not govern just the spatial synopsis of the video but the temporal one as well. A bell announcing the arrival of the lift rings again and again and even the broken fluorescent lamp in the hotel corridor flashes repeatedly.

That this principle has not been chosen randomly is evidenced by the pivotal meaning of this work, which should be sought in a detail of a poem in a book laying on a hotel room table. It is the poem One Art by the American modernist writer Elizabeth Bishop. What is especially important in this respect is the form – the villanelle, a difficult poetic shape, consisting of six triplets and a single concluding verse. And just as the rhyming words are repeated in the poem One Art, the shots with duplicated images are repeated in the Authoress video. The rhythmic movement of the floors from the hotel lobby sequence corresponds with the rhythm by which the video is segmented into several separate parts. However, the relationship between the Authoress and One Art is not merely formal. Bishop writes about the “art of losing” proceeding from an ordinary loss of things or direction to loosing somebody close to her: “The art of losing isn‘t hard to master; / so many things seem filled with the intent / to be lost that their loss is no disaster. //...// – Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture / I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident / the art of losing‘s not too hard to master / though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.”

The meaning of the poem is hidden in the inner unity of art and loss, completeness and emptiness. Bishop attempts to balance her grief over the loss of an intimate friend by mastering the poetic form which, nevertheless, totally collapses at the end. On the other hand, it is a valid premise that every piece of writing represents a loss of some kind, as syntax implies the acceptance of emptiness as not an external, but rather an internal condition of every sense. The tension is amplified by the selection of the two voices through which the writer addresses us: in the first three triplets it is a voice in the second person singular, in the next three triplets she speaks to herself in the first person. In the last, concluding, verse, the second person briefly returns in a bracketed formulation – accentuated by using italics (“Write it!”). The ambivalent union of art and loss, connection and division, is present in the very notation of the last verse of the poem, when Bishop breaks up the strophe inserting a bracket and a doubled “like”.

The voice of the Authoress video is equally doubled. The neutral, static takes in the first part are interspersed by volatile subjective views as the image-based travelogue matches the descriptive traveller’s style of Bishop’s writing from the anthologies Questions of Travel (1965) and Geography III (1976), which also includes One Art. In the second part of the video, subjective views from the hotel window form a backdrop to reading a letter from Lima. It is the letter that represents the “art of losing” as during its writing we are with the person who will later read it, and vice versa the person who then reads it remembers the one who wrote it. This is also the reason why the voice in the video is doubled, when it is first read by the writer, then the addressee and finally their voices resound in unison. The role of the lonely imperative “Write it!” from the close of the poem is substituted in the video letter by the final “You know”. The theme of relationships resurfaces most powerfully in the final part of the video, composed of still images of a waiting man and woman. Just as the letter referred to the previous section, when it described the arrival at the hotel, it simultaneously anticipated the final section. While the man waiting in front of the house is looking into the camera, the woman is in a dialectic juxtaposition filmed inside the house from behind, as if turning to him. In the first image the woman is slightly leaning with her right hand on the door frame while her right leg is bent, as is usual during a long wait. In the final shot we see her resting against a wall, although her look is still fixed outwards, as is suggested by her tense nape: “Lonely authoress”.

— Karel Císař [In: Labyrint 31–32 (2012), Labyrint – Via Vestra, Prague, 2013, p. 88. ISSN 1210-6887]

Tereza Sochorová & Filip Cenek: Authoress (2008, video, 9:15 mins)

Video (on-line): http://intermedia.ffa.vutbr.cz/spisovatelka-authoress