4/11 2015, Den otevřených dvěří Ateliéru intermédií FaVU VUT Brno, 13:00–19:00, Údolní 19.

První ateliérová schůzka je ve středu 23/9 13:00, místnost 316 (Údolní). Prosíme o dochvilnost!

Novým vedoucím ateliéru bude od 1. září 2015 umělec Pavel Sterec.

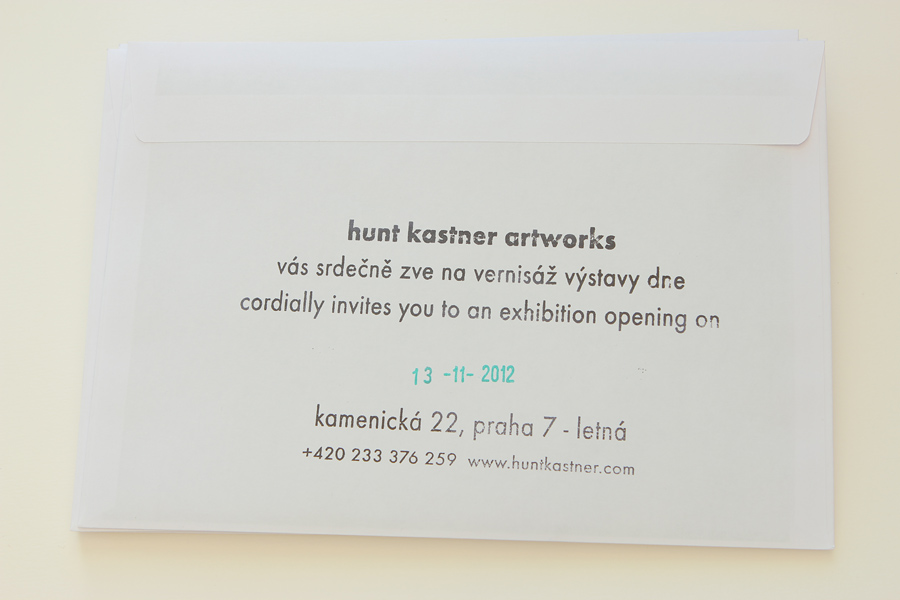

Overlay | Překrývka (hunt kastner)

Overlay | Překrývka. 14/11 — 21/12 2012 | 13/11/2012 18:00; hunt kastner artworks, Kamenická 22, Prague; http://www.huntkastner.com

This exhibition was supported by Ministry of Culture, Czech Republic.

An installation comprised of photography, still images and light projection. An open-ended story, which naturally questions and emphasizes its own failed delivery (a chain of continually intertwining relations). Just as with the Japanese architect, Tadao Ando’s, A Wedge in Circumstances, however, this should not be seen as abstraction, but a prototype.

Installation views by Ondřej Polák

■

“It’s a somewhat minimal show,” says gallerist Katherine Kastner of Filip Cenek’s solo exhibition Overlay. Her need to state this fact is understandable. Given Cenek’s background in audiovisual studies, cinema projectionist training and interest in nonlinear narratives and indeterminacy, one might well imagine a kind of Michael Snow meets Tony Conrad scenario. In truth his method is much more pared down – minimal. ——— The show is composed of one black-and-white photographic image, repeated three times: next to a winding path by the shore, a child sleeps on a thin mattress, shaded by a grove of trees. A landing (fishing) net is propped up close by and he is surrounded by beach sandals and knapsacks; the personal debris of a family’s day by the sea. Two iterations of this image, identical in scale at 100 x 130 cm, are propped against the main wall of the gallery. In front of them stand two projectors, one constant with its clinical white light, the other suffusing the second print with warmer, softer light; the intimate glow of nostalgia. If you stay long enough, you’ll notice that this light fades out, shuts off and comes back on in a cycle of seemingly arbitrary intervals. ——— On the wall adjacent, the photograph is dramatically enlarged, reconfigured as wallpaper; here it takes on a darker, grainier quality, sombre and documentary, prompting you to step back, gain some distance and clarity. But the piece is not lit, except for whatever of Prague’s bleak winter sun makes its way through the front windows. Framed by the light radiating from the space behind it, the image is further obscured as you move away from it. This, along with the fact that one is forced to squat on the floor in order to get a close look at the two smaller prints, seems to stand testament to Cenek’s own reputed ‘discomfort’ within traditional gallery spaces. ——— The photograph itself, as the description might suggest, is somewhat romantic. The image is pervaded by much the same sense as comes from flipping through old family albums, which is where it could well have come from. It defies location in an immediate time and space, allowing for an encounter with an unrestricted audience. No clues as to its deconstruction, no indicators of its history or function are given. Instead, each repetition causes a shift in focus and perception through the alteration of the light, each encounter a shift in the trace of the memory that it triggers, while simultaneously diminishing the trace of the artist as absent subject. It calls into play our experience of the very photograph itself. Overlay then comes to function much the same as images that Jean Baudrillard, in Photography, Or the Writing of Light (1999), refers to as being capable of withstanding the force of imposed signification. The photograph, he writes, ‘simultaneously ends the real presence of the object and the presence of the subject. In this act of reciprocal disappearance, we also find a transfusion between object and subject.’ However, in order for this transfusion to succeed, the object ‘must survive this disappearance to create a “poetic situation of transfer” or a “transfer of poetic situation”.’ This speaks to the force of Cenek’s work, which lies precisely in its ability to ‘touch us directly, impose on us its peculiar illusion’, allowing it to speak at once through the mire of enforced meanings and representations in a language that is intrinsically its own. [...] — Zarmeené Shah (ArtReview 65, January/February 2013, pp. 122–123)